Thoreau’s economics

"The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run"

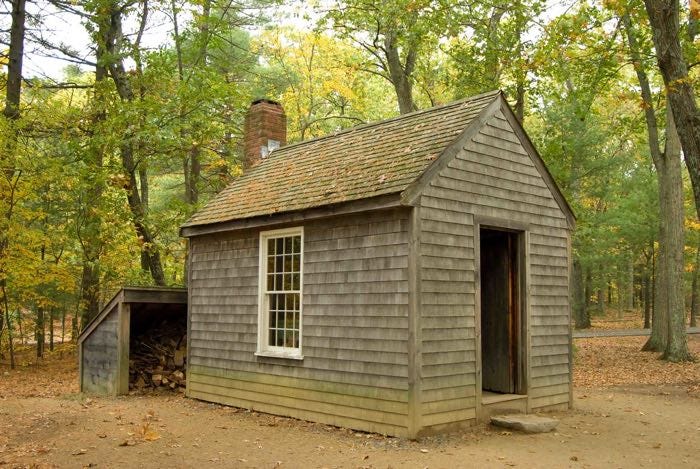

Henry David Thoreau

The above quote is from the book Walden by Henry David Thoreau the same book where he famously wrote: "the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation". Thoreau didn't see work as a way of earning money, instead, he saw it as a way of losing life. Using Thoreau's economics you can calculate the cost of things using "life" as the metric instead of money. For example, depending on your salary, a car that costs £30,000 can translate to one year of your life.

Using life instead of money can make for better decision making and is arguably the more logical way of looking at things, especially when you consider that our time (life) is the source of our money.

Whenever we want that new thing, whether it be a car, bigger house or bigger TV. We forget the consequences when thinking in monetary terms. There's no limit to money, money is infinite, just look at the rate governments and consumers are borrowing it. But our life which is exchanged for that paper being printed is very finite. We have a few healthy decades if we're lucky. This is why Thoreau wanted to analyse the true cost of goods and services. For Thoreau, the idea of wasting life in exchange for owning more stuff was a terrible deal.

Thoreau’s new economics is written about in Cal Newport's Digital Minimalism. I found the below extract about lavish farmers particularly enjoyable.

[Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport]

Thoreau was able to satisfy all of his basic needs quite comfortably with the equivalent of one day of work per week. What these farmers are actually gaining from all the life they sacrifice is slightly nicer stuff: venetian blinds, a better quality copper pot, perhaps a fancy wagon for traveling back and forth to town more efficiently. When analyzed through Thoreau’s new economics, this exchange can come across as ill conceived. Who could justify trading a lifetime of stress and backbreaking labor for better blinds? Is a nicer-looking window treatment really worth so much of your life? Similarly, why would you add hours of extra labor in the fields to obtain a wagon? It’s true that it takes more time to walk to town than to ride in a wagon, Thoreau notes, but these walks still likely require less time than the extra work hours needed to afford the wagon.

It's clear that things haven't changed over the centuries. Just as farmers were seduced to buy better blinds and over-consume in the 17th century, it's the same story with Amazon in the 21st. Moreover, a better copper pot didn't make you happier back then and nor does the latest mobile phone today.

Just as Thoreau did, we need to ask: is giving up our life in exchange for material goods and services a fair exchange?